Contributing to Clojure

In the spirit of the classic “How A Bill Becomes a Law”, I’d like to give some insight into how a Clojure question or JIRA ticket becomes a commit in the Clojure code.

Users and contributors

It’s important to start with the distinction between users and contributors of the language. The pool of users is large and many people happily use the language without needing to file a problem or a request. When a user does encounter an issue, they often may wish to provide a problem report or an enhancement request but not have the time or inclination to do the work themselves (which is totally fine!).

Separately, there are contributors to the language, both people on the Clojure core team at Nubank, and people in the community, who are interested in helping. Sometimes they are scratching their own itch, and sometimes they are involved in the great effort.

For many early years of the Clojure ecosystem, we used a single tool for both audiences (JIRA, and before that other similar systems). In 2019 we decided to create a new system for users to ask questions about Clojure (which may be problems or requests, or other things) at Ask Clojure. This site authenticates via GitHub (which most developers can do these days), allows for search, suggested similiar questions, categorization, keywords, voting, and discussion. We ask that Clojure users file problems with the “problem” tag and requests for enhancements with “request”.

We also continue to maintain the Clojure JIRA issue system for contributors (but this site is public so everyone can view). This site was migrated from an on-prem site (provided free by Contegix) to a cloud instance (provided free by Atlassian). We greatly appreciate the services provided by these companies to support the Clojure project. The cloud account has a max user limit so we took this migration point as an opportunity to update the pool of authorized accounts on this system. Anyone that had provided a patch on a JIRA ticket on the old system was automatically migrated over, other users were not.

How are Ask questions and JIRA issues linked?

Given that there are two systems (Ask Clojure for users, JIRA for developers), these systems must be coordinated. When Ask Clojure was created, all JIRA issues open at that point were also made into Ask Clojure questions. Automated categorization and tags were created from existing projects and labels and some ad hoc work was done to clean that up. All Ask Clojure questions associated with JIRA tickets have a comment with the linkage and is tagged with the “jira” tag.

The Ask Clojure site is monitored by the Clojure dev team and we try to respond within a day or two. If you are looking for someplace to help, answering questions on this site is amazingly helpful! Sometimes questions can be directly answered, sometimes they seem like issues that should be filed. If the core team decides a JIRA should be created, we do so and put a link to the Ask Clojure question at the top of the JIRA description, and a link to the JIRA in an Ask Clojure answer (and tag the question with “jira”).

If you are encountering an issue and find an existing question for it, PLEASE up-vote the question and drop a comment so we can tell what people are encountering. Even very high voted questions in Ask Clojure have 10s of votes. The core team periodically reviews the problems and requests of highly voted issues, looking for common user problems and prioritizes these for work. This is an important feedback mechanism.

When JIRA issues are closed, we also update the Ask Question, and often mark it closed as well. This is a somewhat imperfect system. If you see something that has drifted, please let us know.

You might be asking - wouldn’t it be better if there was one system? Yes, but we haven’t found one that does just what we want and we’ve found this to be a workable compromise.

Becoming a Contributor

If you’d like to provide patches, you will need to become a Clojure Contributor. Contributors to Clojure are required to jointly assign copyright on their code to Rich Hickey, the creator of Clojure. Having a single copyright owner for the entire project allows it to be defended against legal challenges and also to make later licensing changes without needing to obtain additional permissions from individual contributors. For more on the details, see the contributors page or the OCA FAQ (the Clojure CA is based on the old Sun CA which later became the Oracle CA… whew).

To become a contributor, you need to electronically sign the Clojure Contributor Agreement form. Within a few days after that (we batch these up), you will be added as a contributor on the contributors page.

If you have a patch to provide on an open Clojure JIRA, you will then need to request access to JIRA by completing the contributor support request. Note that access will generally only be provided if you have already signed the CA, and you are providing a patch. If you wish to file an issue, comment, or vote, please use Ask Clojure.

Speaking of patches …. Clojure and the contrib projects only accept changes via patches attached to JIRA tickets. These projects do not use GitHub issues or accept GitHub pull requests. We realize that this can be jarring for developers used to contributing to other open source projects.

The pull request model optimizes for ease of contribution. However, Rich has made the point in the past that he prefers to optimize instead for the management/assessment side of the process where his preferred workflow is more efficient working with patches.

Working With Tickets

There are three kinds of issues: bugs (something doesn’t work), enhancements (improvements to existing features), and features (new functionality).

New tickets will have a number of fields to complete:

- Summary - a concise description of the problem

- Priority - defaults to Major, but usually the development team uses this truly as a priority (not a severity) that may fluctuate during the lifecycle of the ticket. Don’t worry about it too much.

- Affects Versions - it’s important to specify which version you found the problem in. It’s not critical that you check every other possible version, just let us know where you saw it. If you’re filing an enhancement for new functionality, just use the latest stable version.

- Environment - if there are important details about your java version, operating system, etc, leave them here.

- Description - this is the place for the real description - more on this in a bit.

- Attachment, Patch - provide patches.

- Labels - it’s ok to leave this blank and let us apply standard labels but try to use the major component (reader, printing, etc) - DO NOT use “bug”, “enhancement”, “patch” or things that covered by other existing fields.

The heart of writing a good ticket is of course in the Description and there is a more written about this in Creating Tickets. Generally we like these descriptions for defects at filing time to include:

- Statement of the problem

- Example demonstration - show the incorrect behavior and indicate expected behavior if it’s not obvious. In 99% of cases, this should be a demonstration at the REPL, NOT a link to a github repo or a gist or anything else.

If the ticket also has a solution, then the description should include:

- Cause - the identified cause of the problem in Clojure

- Approach - how the cause should be fixed and discussion of alternative approaches that were not chosen and why

- Patch - name of the “current” patch - it’s hard to keep track sometimes!

Often new tickets will not include these sections and they will be added later as people work on the ticket.

Here’s an example of what a description might look like (this is not an actual bug of course):

Adding odd numbers doesn’t work.

user> (+ 2 2) 4 user> (+ 1 3) ClassCastException

Cause: Never implemented odd number adding in the Compiler! See the missing branch in FooExpr.

Solution: Fully implemented the branch for odd numbers to be just like even numbers. Considered just getting rid of addition altogether but I guess people use it.

Patch: add-odd-3.patch

In general, it’s helpful to keep all of these sections as minimal as possible so that later when someone new picks up the ticket, they see exactly the right details to understand the actual/expected behavior and how it’s being fixed. Additional information can be added in the comments if you need to provide more background.

Ticket Workflow

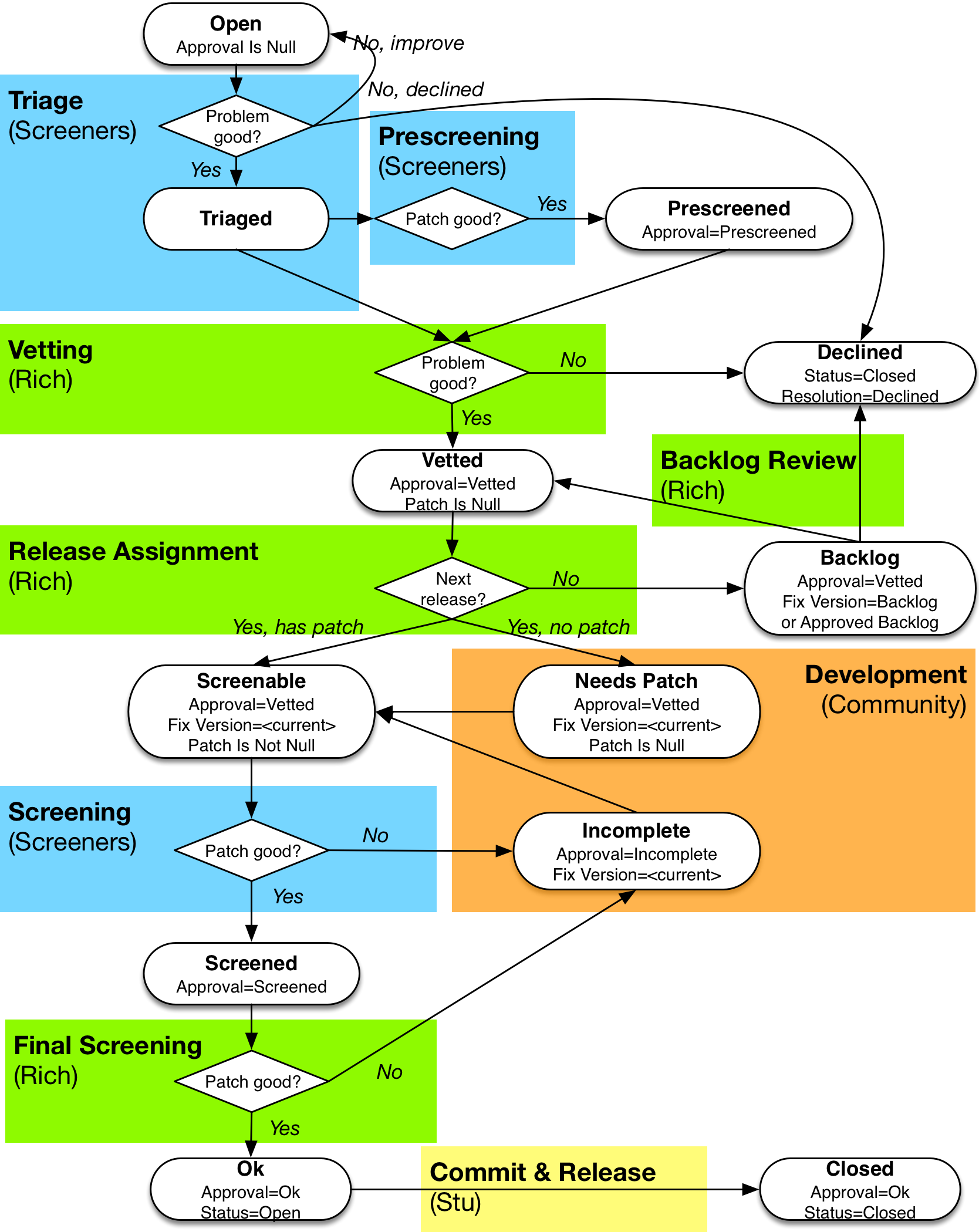

There are a number of ticket “states” defining the ticket workflow, demonstrated in this diagram from the workflow page:

As a contributor, the primary place where you get involved is the orange block where patches are being developed.

Tickets generally go through the following processes (these are the colored blocks). As tickets move they land in different states (the rounded corner boxes). Most processes involve some person or group making a decision (the diamonds).

- Triage - screeners review tickets as they arrive and consider the question: “is this a good problem to work on?”. If the answer is yes, the ticket is marked as “Triaged” in the Approval field and the ticket moves to the Triaged state. If the answer is no, the ticket is Declined or marked as a duplicate. If the answer is maybe, the ticket is left in the open state. Screeners will often also improve the quality of the ticket at this point - simplifying the description, adding labels, and generally making it easier to consume.

- Vetting - Rich periodically (on the order of months) looks at the Triaged tickets and double-checks the work of the screener, which is nearly always ok. He then marks it as Vetted.

- Release scheduling - Rich then evaluates the vetted tickets and decides which release to target. This is nearly always the “current” release, but occasionally the “next” release. This process is often done at the same time as vetting.

Once a ticket has been through these processes, a screener and Rich have both agreed it’s a good problem and have decided when it should be fixed. At this point, things shift to focus on making a patch for the ticket. Sometimes one will come in with the initial ticket, but in the majority of cases, those initial patches are not what ultimately gets applied.

There is a whole page on developing patches but I’ll hit the highlights here. If you want to work on a patch, clone or fork the Clojure github repo and create a branch for the ticket you’re working on:

git clone git@github.com:clojure/clojure.git

cd clojure

git co -b clj-9999Then make your changes to address the ticket. You can run the full test suite with mvn clean test. You can install a new version of Clojure into your local Maven repository with mvn install - this is then accessible for other local builds as a snapshot version. See the developing patches page for lots more detail.

Once everything is ready, you can create your patch like this:

git format-patch master --stdout -U8 > clj-9999.patchThen you can attach that patch to the ticket in work. If I am creating a new version of an existing patch, I often create a fresh branch, git apply the old patch, then work from there.

While in development, the processes are:

- Development - the process above where contributors add patches to the ticket

- Screening - screeners review the patch and decide whether it is a good solution to the problem in the ticket. If yes, then it’s marked as “Screened”. If no, then it’s marked as “Incomplete” with comments about what to change.

At this point, the ticket+patch are ready for Rich to review. Periodically, Rich will review all screened tickets. If the patch is good, it’s marked “Ok”. If it needs more work, it’s marked as “Incomplete” and it goes back into development. Once tickets are marked “Ok”, one of us applies the patch to the Clojure code base, then closes the ticket.

More links!

Virtually everything related to the Clojure contribution process (including every link in this post) is linked and categorized on the workflow page of the Clojure site. For any question, please use that as your starting place!

Thanks…

Every release contains input from dozens of contributors working on hundreds of issues. Thanks to all the contributors for everything you do!!

If you have questions, please raise them on Clojurians Slack in the #clojure-dev room.